Back in time: The lost John Tenta interview:

Back in time: The lost John Tenta interview:

Who is John Tenta and why did this promising Canadian leave sumo wrestling in Japan?

EDITOR’S NOTE (Dorothy Irwin): I had the opportunity to interview the late Canadian wrestler, John Tenta, in 1988 as he was leaving behind a sumo wrestling career in Japan. Tenta would go on to wrestle in the World Wrestling Federation (WWF, later changed to World Wrestling Entertainment or the WWE) as Earthquake. This article has never been published.

John Tenta walked away from sumo wrestling in Japan with just the clothes on his back. He was skyrocketing to fame, leaving many talented Japanese sumo wrestlers in his dust. Then he disappeared.

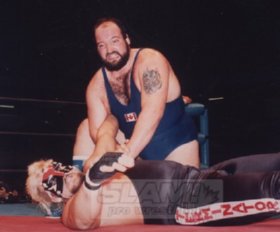

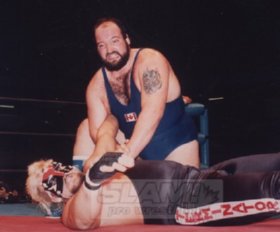

Just as suddenly Tenta burst on the scene as a dazzling favorite for All Japan Pro Wrestling. Wanting to know why Tenta had made such a drastic turnabout in his career, this reporter arranged to meet him after one of his matches near his home town of Surrey, BC.

Watching Tenta walk toward the wrestling ring in his black and green kimono is an experience in itself. The air around him seems to part in waves giving way to his giant stride. He is only 24 years old and has not yet reached his peak strength or performance. He is 6’7″ tall and weighs 410 pounds. His hair is long, but it is pulled up to the top of his head in the traditional sumo top knot. The other wrestlers on the ticket were taking no chances so they didn’t stand still long enough for Tenta to get a real hold on them. He may be a brute in the ring, but outside signing autographs for the children he’s a different person. He reminds you of the main character from the Canadian children’s program, The Friendly Giant.

Speaking with Tenta in the more relaxed atmosphere of his parents’ home, his mother fusses over him wanting him to get comfortable in an easy chair before she goes to the kitchen to put the coffee on. The living room reflects bits of Tenta’s life in Japan: dolls in glass cases, commemorative cups, scrapbooks and a suitcase overflowing with clippings that will get organized someday.

“I’ll need a new suitcase for John’s clippings soon,” beamed his mother.

Tenta spreads his hands like the conductor of an orchestra as he begins telling how sumo wrestling changed his life. The Japanese were anxious to have him in sumo after they saw his skills at an international tournament in Chicago. Negotiations were completed with great ceremony in Surrey and then Tenta was whisked away to Japan. He was met by a large delegation led by his promoter, referred to as a “Stable Master” in sumo circles. Other sumo wrestlers respectfully carried his bags as he was led away to a Japanese restaurant. Tenta said he sat on the floor for hours listening to people speaking a language he didn’t understand and eating food that he had never seen in his life and didn’t like at all. Next came the Japanese bath. Tenta was used to taking showers with other athletes, but having someone else soap you down made him feel as if he was being treated like an infant.

“This is going to take a bit of getting used to,” he recalled thinking. “I realized that I’d have to be very open minded and patient toward the things that make up their way of life. I had to learn everything at once.”

Tenta would wake up at 5 a.m. when it was still pitch black outside to start his grueling training in the unheated sumo wrestling gym, called a “stable.” The practice ring was the standard 15-foot circle edged with a twisted straw rope. The surface was hard, packed clay covered with sand. To win a match a wrestler had to push his opponent out of the ring or have some part of his opponent’s body touch the floor. At 5:30, he would work out with a partner. At 6:30, it was time for pushing exercises against the outstretched arms of an opponent. At 7:30, he would work with his Stable Master shuffling low around the ring and rolling on the floor. At 8:00, it was arm exercises followed by training within his division at 8:30. At 9:30, the other divisions would train while Tenta would watch with his arms folded. At 10:30 he would do leg exercises, calisthenics and stretching exercises. This time was also allotted for practicing sumo slogans and songs. At 11:00, the higher division wrestlers would go for a bath while the lower division wrestlers were to act as their servants or sweep the floors. The duties as a servant included washing the senior wrestler, getting his clothes ready, assist the wrestler out of the tub and dry him, dress him, take him to lunch, fill his plate and glass, take him to have his hair done and then take him to his room. Afterwards it was time for the lower ranked wrestlers to bathe and eat lunch. The afternoons were filled with classroom study and tournaments, while evenings consisted of many public relations events including dinners and parties.

As Tenta went through the divisions, he won 24 straight matches which he said is a record for a foreigner. Tenta was rising quickly through the divisions. Every minute of his day was accounted for. One of the things that bothered him most were getting only two meals a day which consisted mostly of stew, pork or chicken, rice and vegetables.

Tenta enjoyed sumo wrestling as a sport but some of the training methods he couldn’t understand. His Stable Master always wanted him to attack with his head. Tenta didn’t like that idea at all.

“I met a fair amount of prejudice,” remembered Tenta. “Here I was a white boy beating up everybody. I was getting special treatment from my (Stable) Master. They knew I had a girlfriend (which I wasn’t supposed to have because of my low rank). I was getting lots of media attention too. Lots of Japanese guys had left school at 14 years old and were my age and they were getting nowhere in sumo. So you can see how it caused hard feelings.”

More and more Tenta felt that his own personality was being erased. Not only that, they also wanted to literally erase the tattoo from his arm.

“They were going to take my tattoo off with lasers,” explained Tenta.

Tenta’s mother contacted doctors in Canada who said that her son would need at least six weeks of recovery before he could start to work out again. Tenta knew that his Stable Master would never let him stay out of tournaments for that long. Tenta talked to the doctor who was going to do the operation, but was horrified to learn that the man had never removed a tattoo before. This made him more uneasy.

Tournament time was also the time for showing the sumo wrestlers off to their adoring public. Almost every night there were dinner parties that lasted until midnight or later, yet the men still had to attend practice the next day at 5 a.m. There was a lot of pressure on Tenta to remain undefeated.

Tenta would beg his Stable Master to let him rest. He felt he was being displayed to the public as this great, foreign sumo wrestler, but in reality he was losing sight of who he really was.

“I felt as if I was on show and tell,” reflected Tenta. “I felt more like a clown or like some kind of hostess.”

Then there was the matter of money. Tenta was working his way up through the ranks, but he didn’t have any money of his own. He would get some money for winning championships, but it came in small amounts. Other wrestlers would give him money, but Tenta didn’t like to take money from other people. If he had been injured and not able to compete in the tournaments, he wouldn’t have been given any money until he was well enough to compete again. In time, Tenta would have been in the high ranks and he would have possibly become a multimillionaire, but he felt that it was too much of a gamble. He had seen guys retire from sumo after 10 years with no education or other skills and be at a dead end. Tenta was preoccupied with these thoughts. His confused state of mind was affecting his training.

“I didn’t see that I was in my best condition for the next tournament,” said Tenta. “I didn’t see any break coming. I decided it was time to go.”

So one day just before he was supposed to go to a dinner party, Tenta walked away with just the clothes on his back and headed for the only person he knew who spoke English, his girlfriend. Then he took a train to Tokyo and joined up with All Japan Pro Wrestling.

“The main difference between sumo and pro wrestling in Japan is that with pro wrestling, except for the training and bouts, your time is your own,” explained Tenta. “There are times you have to do what your boss says, but any job has that. Compared to another job this is pretty easy for me.”

Tenta still trains hard. There are long sessions of weight lifting, running outdoors and working out with other wrestlers.

“I don’t have a special coach,” compared Tenta. “I learn a lot from other wrestlers. Just like playing a chess game, moves have to be planned well in advance.”

Training is hard to maintain when Tenta comes home to Canada twice a year. All of his mom’s home cooking including fresh bread hot from the oven, pecan pie and fruit cake made from the secret family recipe, has proven to be too great a temptation.

“My ideal weight is 350 to 360 pounds,” remarked Tenta. “When I feel the pounds packing on I go training on the hills. Right now my weight is about 390 so when I go back to Japan I’ll train and lose that weight again. It’s funny but in training for pro wrestling we eat the same stuff as I did in sumo, but now I like it.”

Tenta brought out a stack of Japanese magazines and leafed through them from back to front, the way they’re printed. He stopped now and then to point out the good and the not so good shots.

“I’ve had a lot of media coverage,” said Tenta. “Mostly good. If the media don’t like you, they print bad pictures of you.”

With a sweeping motion of his arms, Tenta draws attention to the variety of matches he’s had in pro wrestling.

“I’m meeting all the top guys,” he explained. “In Japan I’m getting some of the best training in the world.”

Sumo has left its mark on Tenta and has made him a more mature person. When asked if he uses any of the things he learned from sumo in pro wrestling, he shakes his head.

“When I go into the ring,” Tenta explained. “I don’t do anything to do with sumo. I don’t walk in wearing my kimono or do any of the ceremonies or anything. In the ring I won’t do a sumo tackle. Instead I do a football tackle.”

Tenta laughed easily as he gathered up the magazines and put them back in the suitcase. He drifted into talking about how different wrestling was in the old days of people like Whipper Billy Watson.

“Wrestling now is a lot harder on the body,” Tenta commented. “There are more dangerous moves, bigger falls.”

Tenta recalled a recent match in Canada where he had been hit over the head with a chair.

“It’s all part of the business,” he explained when asked what he thought of the rougher style of wrestling. “You have to take what the other guy gives you. You’ve got to come back and give it right back to him. You just look at it as his technique.”

The conversation swung back to Japan once more.

“Pro wrestling in Japan is the way I always imagined professional wrestling to be,” remarked Tenta. “Over there I wrestle as a Japanese. Even when we travel around the country by bus I travel with the Japanese, not the Americans. I’m very happy in Japan and I have a lot of fans. My promoter [Giant Baba] and I get along really good. He’s a real giant — 6’8″, weighs 200 pounds and he gets a lot of respect. He’s going to get me to the top.”

Tenta received the Rookie of the Year award and is well on his way to reaching his goal. It hardly seems possible that this young Canadian could have come so far in wrestling in just a few short years. I asked him what gave him the push in that direction to begin with. Tenta shifted down into his chair a little further to get more comfortable before he started telling the story:

“It really started when I was just little. I used to get up early on Saturday mornings and watch cartoons. But after a couple of hours my Dad would get up and change the channel to wrestling. I’d go to my room and read. One day I got mad about it and I stayed to see what my Dad thought was so good. That’s when I got hooked.

Read the rest of the interview here:

http://slam.canoe.ca/Slam/Wrestling/2013/07/07/20957291.html